‘Outlaw’ Vibe Comes through In HIs Music

By Ellen Miller Goins

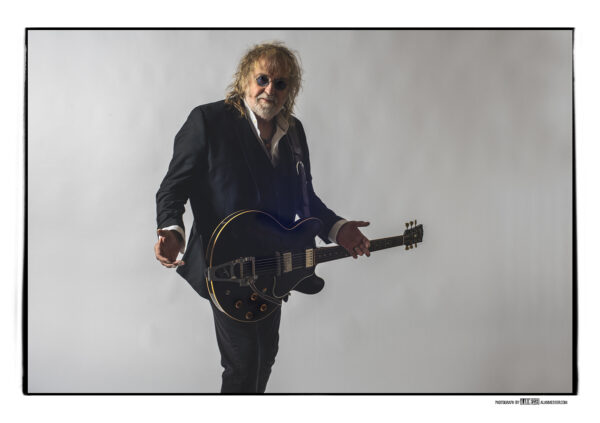

Since age 3, singer-songwriter Ray Wylie Hubbard has made a few bargains with God, but at 42 a year after he decided to get sober he bargained with himself: Proclaiming he wanted to be a “real songwriter”, the musician swallowed his pride and took lessons to learn the intricacies of blue guitar fingerpicking from Sam Swank.

write songs to get Clint Black or Garth Brooks to record them. I was just going to write the best song that I could, and hopefully that would contribute to someone’s enjoyment, you know? And so, that kind of turned it around for me . … I actually started having a semblance of a career.”

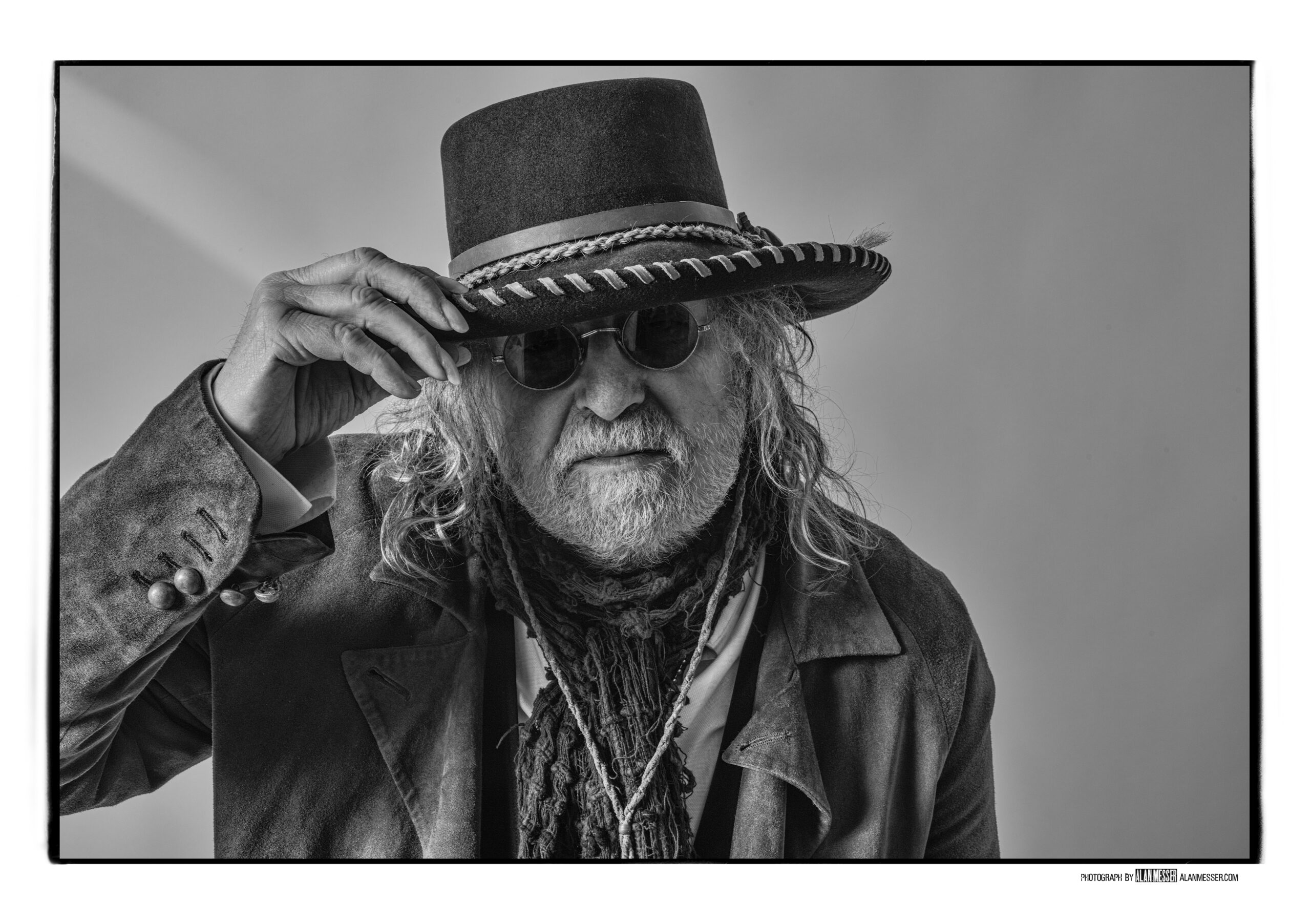

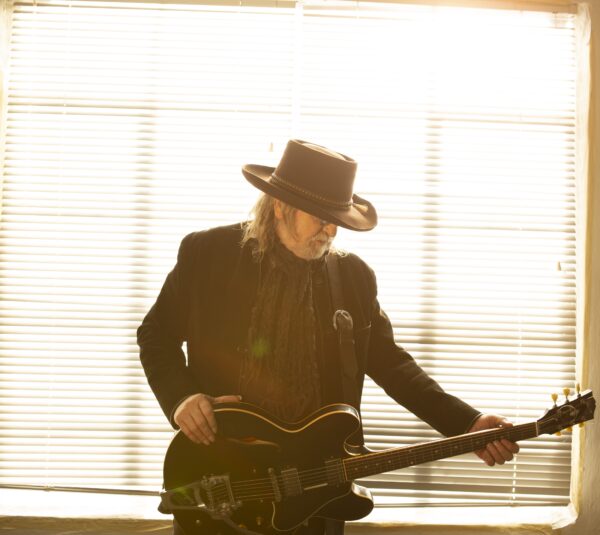

Despite being clean and sober for over 30 years, Hubbard still has a reputation as a rebel – these days, though, he’s more of a maverick with his writing. At 77, he still looks the part with long, wavy hair, worn blue jeans, an impish smile. His often self-deprecating sense of humor comes through in conversation – and in his music.

As a younger man, Hubbard wrote, “I thought of myself as a Keith Richards cool drug rocker, a Townes Van Zandt tortured songwriter, a Dylan Thomas heartbroken poet. The reality was that I was just a sloppy blackout drunk playing, ‘Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother,’ twice a night in these shitty honk tonks and seedy bars … where the patrons drank like I did.”

Longtime fans -those who can belt “up against the wall, Redneck Mother!” -might protest, knowing that Hubbard’s roots in New Mexico go all the way back to the late ’60s and early ’70s – and knowing that song was penned injest after an unfortunate encounter in a Red River Bar. He notes, “Whenever you write a song, [think] ‘can I sing this for 38 years?’ But it’s been 50 years now!”

He had his run in with a “redneck” and his mom who were none too happy the day he came into the D-Bar-D (now the Motherlode) in Red River to buy Miller High Life. Barely escaping a threatened beating, Hubbard returned to that night’s “hootenanny” and played the song thatfor better or worse -would become his trademark song.

“Then, [Redneck Mother] was the only thing I was known for, so I’d go to these old honky tonks and they’d yell, ‘play Redneck Mother’, and I’d play Redneck Mother. Then I’d say, ‘Here’s another song I wrote,’ and they’d go, ‘play Redneck Mother again!’ But now, it fits in the arsenal, because I’ve got these other songs, you know, like Drunken Poet’s Dream, Desperate Man, Wanna Rock and Roll, Snake Farm, and Bad Trick … so it fits good, because … I feel like it’s well written.”

ROAD TO RED RIVER

An Okie by birth, by high school Hubbard was living in Dallas, and feeling a bit like an outsider when he recalled seeing Michael Murphey play with his folk group at an assembly. He started playing music with classmates Rick Fowler and Wayne Kidd. “I then found Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly and Jimmy Rodgers and Cisco Houston,” Hubbard wrote. “I was now a folkie; I got me some desert boots and a work shirt.”

After high school, they ended up in Red River. “We saw a little sign on the bulletin board that said ‘entertainers needed for ski resort’, so we auditioned and found out it was a guy named TA Painter who had rented the ski area up in Red River for the summer to do barbecue; so we got on a bus there in Dallas, with two guitars and a banjo and a couple of suitcases and, 26 hours later, we got off in Questa. We stopped everywhere.

“[Painter] picked us up, took us to Red River, and said, ‘Boys, there’s something a little more than just playing music. One of you is going to have to wrap potatoes in tinfoil. One of you is going to have to mop, so we had all these other jobs we had to do . … But we really fell in love with the area. We kept coming back to Red River.”

They did gunfights at Frye’s Old Town. “I put on an old cowboy hat and strapped on a six gun with blanks and became Silly the Kid and, along with Texas Red and Black Jack Ketchup, we’d rob the falsefront bank, forget to take the money, and then have a shootout where I get hit and fall of the roof.”

They took visitors on Jeep tours and made-up “facts.” Quips Hubbard, “That cave there is where Billy the Kid used to hide out.”

The boys played for Jack’s Riverview Cafe and Motel before opening their own alcohol-free nightclub, The Outpost, where they performed as Three Faces West. Their presence in town helped cement the link between the thriving “outlaw country” rock scene in Austin and Red River (and later Taos)- and it’s one that remains to this day.

Jerry Jeff Walker came into town, and everybody was real excited . … ‘Wow, Jerry Jeff’s here, the guy who wrote ‘Bojangles’! This is going to be so great for the town! And then about three days later … ‘When do you think he’s going to leave?’

“It seemed like a lot of the musicians from Austin would come up through Red River on the way to Colorado, and then Steve Fromholz and Dan McCrimmon from Colorado would stop off on their way to Austin, and, of course, Michael Murphy played up there.”

Hubbard left to tour, eventually forming Ray Wylie Hubbard and the CowboyTwinkies, and began his well-documented slide into addiction, followed by redemption, a new career path, and a new life with wife Judy.

THE TAOS CONNECTION

Around the same time they were playing in Red River those early years, Hubbard recalls, “Garnet Frye would bring us down to Taos, and there used to be two little bars right on the plaza, and … they had these two musicians that played Spanish songs and flamenco, and we’d get to drink beer with them, and so that was kind of our first experience with Taos, and for an 18-, 19-year-old kid, it was great! It was magical in a way. Taos attaches to something within you. It just gets in your blood.”

Hubbard has come near full circle having moved to Taos late last summer, though he and Judy kept the cabin they restored in Wimberley, Texas. In Taos the couple found a retreat from the Texas heat where Judy, a master gardener, could grow herbs and other plants. We came up here, and just saw this place. The garden was just beautiful! We’re very fortunate right now. We’re gonna keep both. We found out that we can make it through the winter here . … but the days are just beautiful!”

A LIFE WELL READ

Called a “songwriters’ songwriter,” Hubbard is humble and a little embarrassed by the attention. Still, he willingly mentors up-and-coming songwriters and continually hones his craft. Honestly? Nobody can tell his story better than Hubbard can. “A Life … Well, Lived” has laugh-out-loud writing that, at the time, betrays an upbringing steeped in literature. “My dad was an English teacher, and so when I was a kid, he didn’t read me ‘The Three Little Pigs,’ he’d read ‘The Raven,’ and he got me into literature: ‘read “Tale ofTwo Cities'” … ‘read “The Last of the Mahicans'” … ‘read “Tom Sawyer,'” … And then we’d discuss them at the table.” He uses literature and out-of-the-blue flashes of inspiration to pen songs that are poetic, songs that are funny, songs with the folksy-blues vibe he loves so well.

“I think Flannery O’Connor said, ‘never second-guess inspiration. When you get that, don’t doubt it. You know, there’s this old snake farm down there in New Braunfels between Austin and San Antonio, and I’ve driven by probably 10,000 times … and one day I just drove by and went, ‘oh, that just sounds nasty.’ That was inspiration, but now what I do with it, that’s the craft. As a writer, that shark is never sleeping.

“I took lessons and learned how to finger pick, and then I learned slide, and then I learned mandolin, and by learning new things, that gives the song a door to come through that wasn’t there before. If I hadn’t learned open-D tuning, I wouldn’t have got ‘Train Yard.’ If I hadn’t learned open G, I wouldn’t have got ‘Polecat’ or ‘Hummingbird.’ So I keep trying to learn new things, which Judy says is all well and good, as long as I don’t try to learn banjo or fiddle!”

Although he’s collaborated songs, including “Desperate Man,” co-written

with Eric Church (look for Hubbard acting in the video), Hubbard says

he is not keen on the “cliche city” songs that characterize so much modern country music. “I’m very particular who I write with now.”

He’s delighted to be living in the same area as Joe Ely, Eliza Gilkin son, Travis Buster, Mike Hearne, Bill Hearne, and Murphy.

“Murphy was very inspirational in high school and … in the folk scene, but when I heard ‘Blues Rags and Hollers,’ that really got me [to] think

‘I can do this’ because there was so much integrity … they weren’t trying

to polish, and it didn’t need it. It was just like a very raw and greasy and cool. A performance is more important than perfection in the studio.

“I’m an old cat, but it’s still a joy traveling around and playing and, you know, making people smile and laugh, you know?”