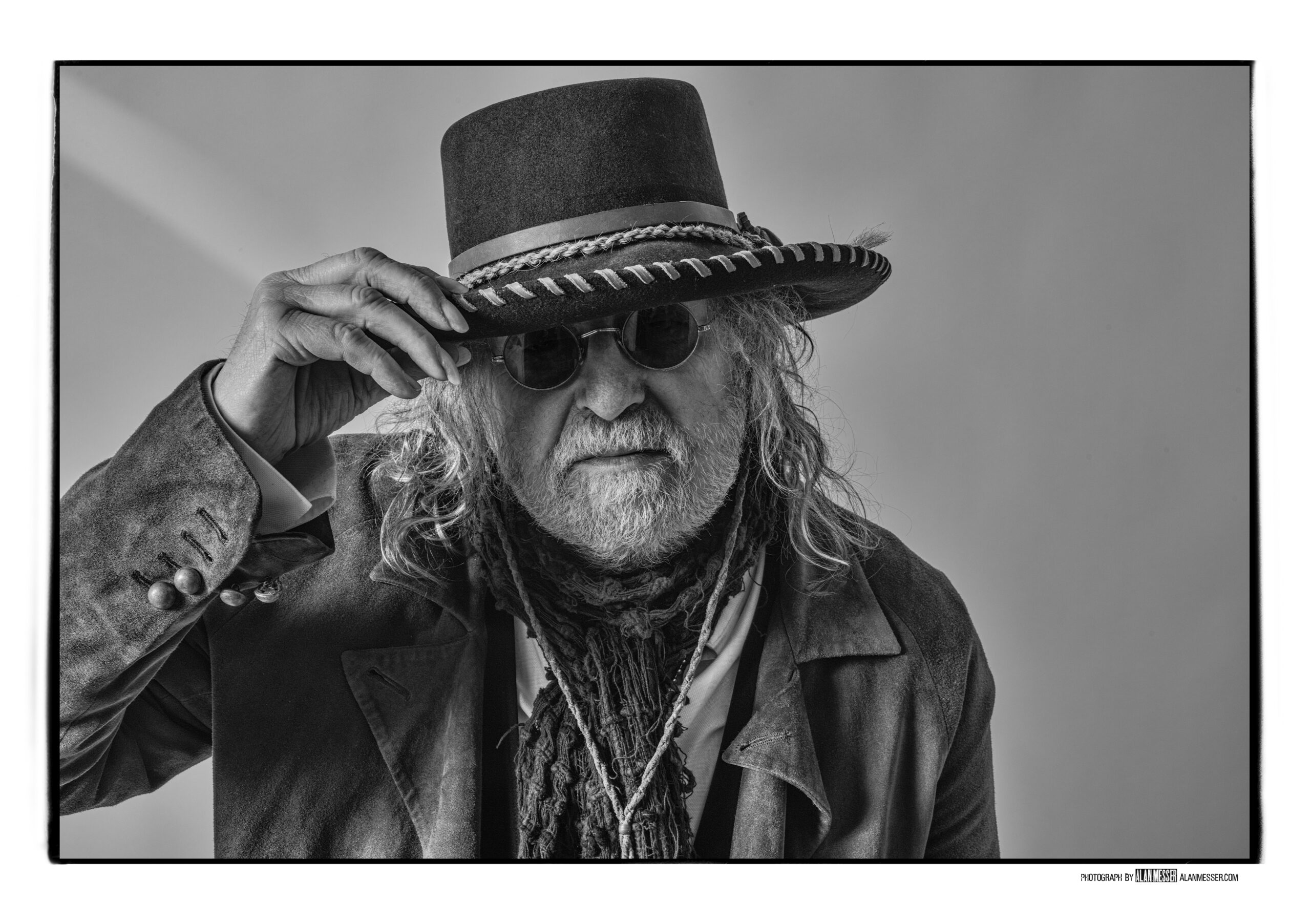

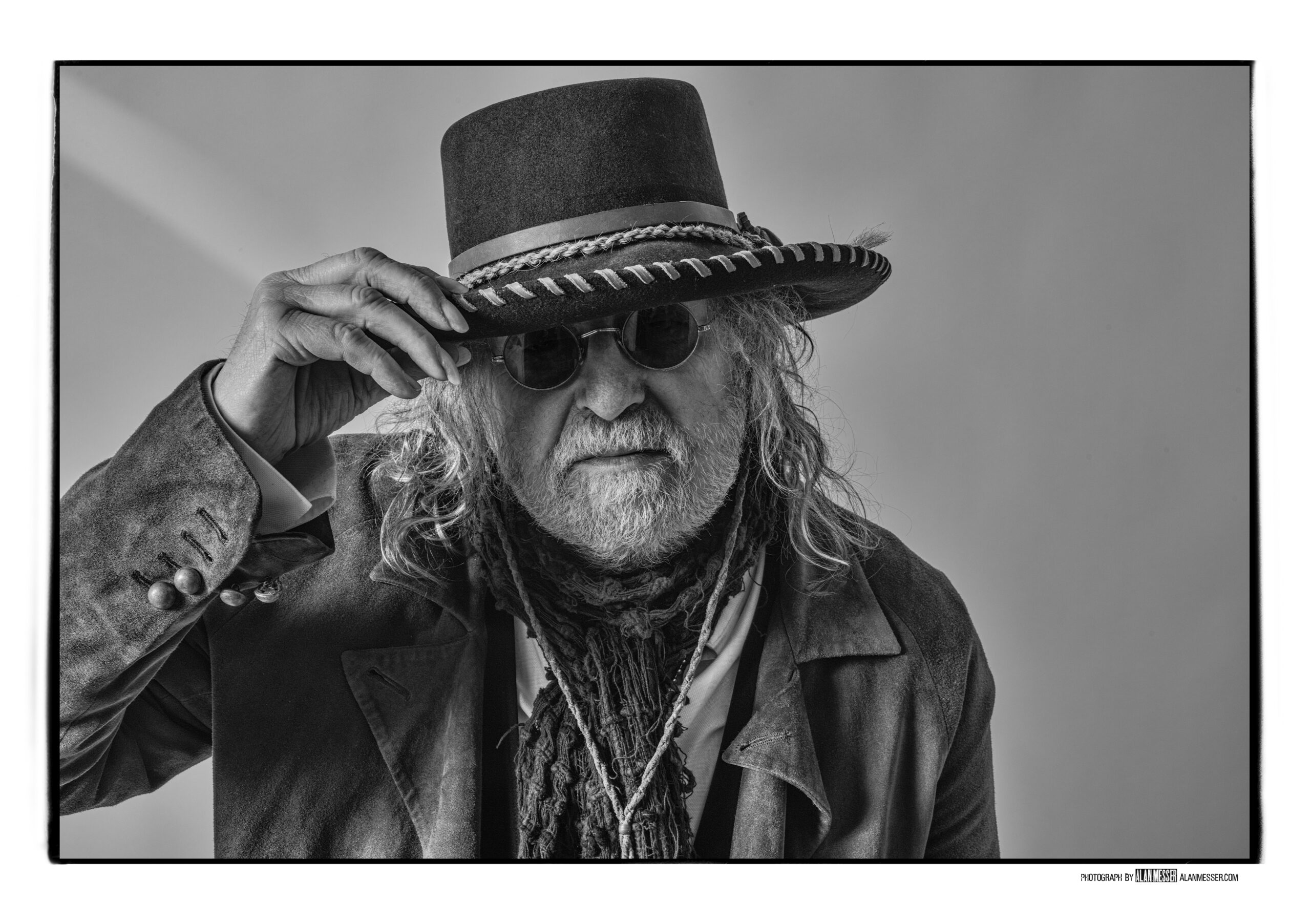

‘Outlaw’ Vibe Comes through In HIs Music

By Ellen Miller Goins

Inspired by the late, great “bad-boy chef ” Anthony Bourdain, who trav-eled the world in search of “culinary hotspots and out-of-the-way gems” we asked some of Taos’ esteemed chefs to share their favorite spots to dine in Northern New Mexico.

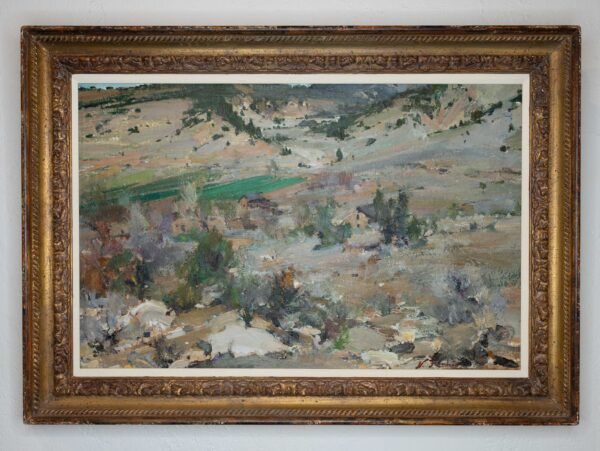

Why head for the nearest museum? These treasure troves off er an educational experience that goes beyond textbooks. Some visitors hope to learn about the past, while others are curious about the community they are visit ing. Some just make a point to enjoy unique art and culture. Whatever your reasons, Northern New Mexico offers myriad opportunities.

Continue reading “Arbiters of the Arts: Greta Brunschwyler “

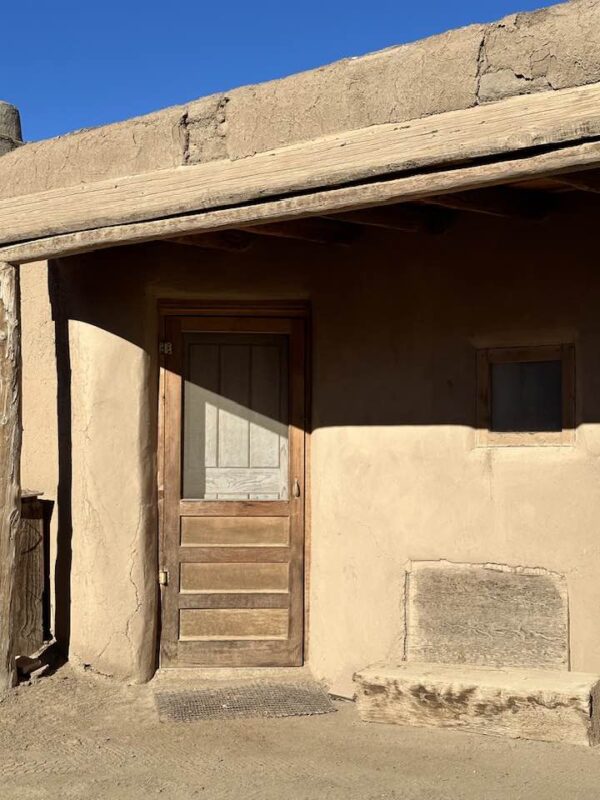

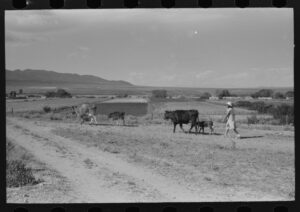

Community has from the beginning been the driving force when it came to settling the region known as Taos Valley. With the Pueblo Peak and a southern spur of the Rocky Mountains holding forth over the occasional hustle and bustle, punctuated by an unmatched serenity, Taos has become a natural gathering place for creatives, adventurers, outlaws, farmers, ranchers and even celebrities from time to time.

The life of Long John Dunn is a study in contrasts and a portrait of resilience.

Dunn was imprisoned in Texas, yet escaped and became known as the King of Taos. He admitted to his own sleight of hand in gambling, but also was a respected member of the Taos community. He arrived in Taos with nothing, but through sheer determination and a bit of luck, went on to own four saloons, a gambling hall, a hotel, two bridges, a livery stable and to control most of the transportation in and out of Taos for close to 30 years. In Max Evan’s 1959 biography of Dunn, “Long John Dunn of Taos: from Texas Outlaw to New Mexico hero,” Evans says, “He lived in his ninety or more years one of the most incredible lives of any of the old-time westerners.”

Dunn almost starved and escaped being killed many times, yet he survived to be 94 years old. What accounts for the near-miraculous life and luck of John Dunn or as he was known in Taos — Juan Largo?